Rosewood History

Frederick Moore’s “White Lion Inn”

While researching this story I was reminded that these early settlement days were indeed the “Wild Colonial Days”. The police courts were busy places.

Name: Frederick MOORE

Occupation: Butcher (1832); Proprietor of the White Lion Inn

Birth: about 1814, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, England

Immigration: 16th October 1832, the Hercules (2) arrived at Port Jackson, Sydney Cove, New South Wales from London 19th June.

Death: 25th September 1883, Seven Mile Creek, Queensland aged about 69 years

Burial: 26th September 1883, Ipswich General Cemetery

Religion: Church of England, Grave number 2674

Father: John MOORE

Mother: Sarah MANNERS

Marriage: 5th March 1854, Ipswich, New South Wales (pre-separation 1859)

Prison Hulk at Chatham

Spouse: Sarah “Sally” FITCH

Occupation: Domestic Servant (1851)

Birth: about 1837, Somersham, Huntingdonshire, England

Residence: 1851, 5 High Street, Somersham, Huntingdonshire, England

(Her parents were living in Rectory Lane, Somersham)

Immigration: 10th September 1852, the Rajah-Gopaul arrived Moreton Bay, New South Wales from Plymouth 25th May.

Death: 8th March 1874, Seven Mile Creek, Queensland aged 37 years

Burial: 9th March 1874, Ipswich General Cemetery

Religion: Church of England B, unknown plot

Father: James FITCH (Agricultural Labourer)

Mother: Ann LEEDON (Laundress)

Children: 9

Sarah Ann MOORE (1855-1948) = Alexander DONALDSON

Fanny Elizabeth MOORE (1857-1942) = James Thomas BURNETT

James Everitt MOORE (1859-1940) = Elizabeth SLUCE

Frederick John MOORE (1862-1943) = Agnes JOCHHEIM

William Samuel MOORE (1864-1952) = Eliza Jane SMITH

George Henry MOORE (1867-1885)

Thomas MOORE (1870-1870)

Robert Walter MOORE (1871-1945) = Margaret Knox STARK

Stillborn Male MOORE (1874-1874)

Frederick Moore was sentenced to seven years imprisonment for larceny at the Nottingham assizes on 10th March 1832. He was 18 years old at the time and was found guilty of stealing stealing 8 gallons of ale and a cask. Ironically, beer was to become a major part of Fred’s life.

Fred was sent to the prison hulk HMS Cumberland on 29th March to await transportation to Australia. The few months he spent on that Chatham hulk would have been grim. In June, Fred boarded the ship Hercules along with another 197 other male prisoners, several of whom were quite young. The youngest was John Smith, a tailor’s boy from Lancashire, who was only 13 years of age. Other passengers were Lieutenant Gibson & Ensign Halket, of the 4th regiment, Mrs. Gibson, master Gibson, Miss Robb, Miss Dobson, John Edwards Esq., 29 rank and file, 5 women and 7 children of the 4th regiment. The soldiers embarked in drenching rain. The weather was so bad that they could not keep dry and some became ill.

The Hercules sailed form London on 19th June. Wittin Vaughan was the Master and John Edwards, the Surgeon Superintendent. Edwards reported in his diary that one of the prisoners had

Newcastle Gaol in the distance

tuberculosis when he boarded but no one noticed because the men were so anxious to get away from the rigid discipline of the hulks that they hid their complaints. However, the progress of the disease was rapid and proved fatal.

The Convict Indents give a description of Frederick Moore. He could read only, was single, Protestant, had worked as a Butcher for 2½ years, was 5ft 6 half inches tall, had a brown and freckled complexion, dark brown hair, hazel eyes, had a small mole on the inside of his left elbow and several small scars on his left thumb.

At Sydney Cove the prisoners were mustered on board by the Colonial Secretary Alexander McLeay, and were landed on Wednesday 31st October 1832. Frederick was taken to Newcastle Gaol and soon after he was assigned to work for Peter McIntyre, a wheelwright at Bolwarra in the Hunter Region (now a suburb of the City of Maitland). McIntyre also grew hops and tobacco. The hops was judged at an exhibition and it was declared that that no similar quality could be produced in this Colony and it is worth three times the value of any imported from England.

Sarah Fitch worked in the family home of the Station Master, Isaac Flory (who had a wife and wife and three daughters), before she immigrated aged 14 years with her parents in 1852, on the Rajah-Gopaul.

It is worth noting the following historical facts about the Rajah-Gopaul:

- When the ship arrived at Moreton Bay, she was not liable to any charges, except for pilotage. This was due to a petition that had been presented to the Queen to enable the separation of the Northern Districts from New South Wales, which was in the course of being signed. Therefore all rates payable under the respective designations of water police dues, harbour dues, light-house dues, entry and clearance charges that would normally occur at Moreton Bay had been abolished.

- The Rajah-Gopaul originally had 353 immigrants, chiefly from the Irish labouring class. During the passage 15 died (12 children) of diarrhoea. There were 13 births during the voyage, so that number who landed at Moreton Bay was 351.

- The sketches Sarah and Aurora brought the immigrants from the ship to the Brisbane wharves along with an order of 450 packs of bottled beer and 20 hogsheads of beer (hogshead = 225-250 litres).

- All of the unmarried male passengers were speedily engaged at wages varying from £25 to £30 per annum, with rations.

- A few of the passengers were ill and one man died in Brisbane Hospital on the night they landed.

- Some of the passengers formally complained about the conduct of the Captain, Surgeon-Superintendent and other officers of the ship, accusing them of immorality and unkind treatment of the sick during the passage. A preliminary inquiry was held by the local Immigration Board (no press allowed), who later put out a public statement that so far as regarded the rumours of immorality on board, nothing whatever was elicited to justify such a report.

While serving his time in the Hunter Valley, Fred Moore got into a bit of strife, which is possibly why he didn’t get his Ticket of Leave after serving his 7 year sentence. In February 1838, Frederick Moore, John Boyle, and Thomas Jenkins, were indicted for causing bodily fear to Richard and Ann Ward while stealing twenty pair of stockings, twenty pair of trousers, twenty shirts, and sundry articles from the Ward’s house. Joseph Thurley was also indicted for siding with and assisting them. The case rested chiefly on the testimony of an accomplice (who was admitted as an informer). His testimony was contradicted by other witnesses and the prisoners were acquitted.

Frederick was finally granted a Certificate of Freedom on 15th August 1842. It is unknown how and when, but he made his way to Moreton Bay where he married Sally Fitch in Ipswich in 1854. I was able to ascertain that they moved to Toowoomba at some stage because on 24th November 1859, this notice appeared in the Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser on page 2.

Notice.

The Undersigned received the undermentioned articles from

Mr. Johnson, Storekeeper, Little Ipswich,

for delivery to Mr. Frederick Moore, Toowoomba.

200lbs Flour; 2 cwt Salt; ½ chest Tea; 1 mat Sugar.

Not being able to discover Mr. Moore’s residence,

the above goods can be had by him at any time by paying

the expense of this advertisement on application to

Mr. W. H. Groom, or Wm. Annand, Senr.

Toowoomba. November 31,1859.

No wonder they could not find Fred Moore’s address because he was living at Seven Mile Creek near Rosewood Gate. A license for slaughtering was issued to Frederick Moore, of Seven Mile Creek on 25th January 1859 by the Police Magistrate at Ipswich. The Moore’s third child was born there in November.

It is possible that Fred Moore bought the property at Seven Mile Creek from Michael O’Brien, when Michael put his residence and land up for sale and moved closer to Rosewood Gate and opened the Rising Sun Hotel.

The Moore’s decided to make their property into an accommodation house or wayside inn. On 7th April 1860, Frederick Moore was granted the license for the “White Lion Inn” at Seven Mile Creek. Six more children were born at the Inn.

It was advertised that Mr. G. F. Forbes, a candidate in the upcoming West Moreton Election, was going to address the electors at Moore’s Inn, Seven Mile Bridge in January 1861.

On applying to renew his licence in April 1861 at the Ipswich Police Court, Fred was granted a license with an “if”. The Inspector stated that there were only five stalls in the stable, whereas the Act required six, and that he had found the beds in a dirty state. Fred pleaded the impossibility of keeping the house always clean during the recent wet weather. The Police Magistrate said he could understand the house being dirty from that cause, but he did not see how the wet weather could affect the cleanliness of the beds. The license was granted, with a caution to provide six stalls, and to have clean beds.

Now that the district had the White Lion Inn, the residents sent a memorial (petition) to the the Colonial Secretary, asking for the establishment of a Post Office Receiving House at Seven Mile Creek. A post office was consequently set up in the White Lion Inn and a separate bag of letters was made up by the postmaster at Ipswich and forwarded to the Seven Mile, as from 1st June 1861.

On 6th November 1861, in the Small Debts Court, Ipswich, F. Moore v. J. A. Nader for £7 19s. 6d. for goods sold and not delivered. Fred Moore was not in court but his wife Sally testified. She said that about three weeks prior she had seen John Anthony Nader, who said that he was going to town (Ipswich), and if she wanted anything he would deliver it for her. Sally said she was going to Ipswich to buy goods and she would organise to get the goods to Mr Nader so that he could deliver them to her. In Ipswich she purchased 1 cask rum, 1 keg brandy, 4 dozen porter, 1 case gin, and 20 dozen lemonade, all of which she saw loaded onto Nader’s dray, with the exception of the lemonade. The same night, about 12 o’clock, John Nader arrived at Seven Mile Creek and called to Mrs Moore from the dray, telling her that he had broken everything but 6 dozen lemonade, which he then delivered to her.

Mr C. F. Chubb, who was representing Nader, said that John Nader was a carrier who had received the articles in town for delivery to Mrs Moore at Seven Mile Creek. Chubb argued that it was clearly not “a transaction of goods sold and delivered” and he wanted the charge amended to “damages for breach of agreement”. The court agreed to the amendment.

John Nader said that after he left Mrs. Moore in Ipswich he started on the road home. When he came to the cutting at Little Ipswich the horses bolted, and though he had hold of the reins, they got away from him and rushed down the road as far as Roberts’ public-house. When he caught up to them he found the dray capsized, the shaft horse lying down, and everything smashed with the exception of some lemonade. After some time he got his horses together and started for home. When he got past O’Brien’s at the Three Mile creek, the horses ran against a tree, and about 9 o’clock he arrived at Seven Mile Creek, his dray getting stuck in the swamp near to Moore’s public-house. He left the dray and went up to Mrs. Moore, and told her all that occurred, and asked assistance, but could get none. Next morning he took all that was left up to Moores but he never got paid. He said he often brought things from Ipswich for Mr. Moore, but never got anything for it; he did it to oblige him. Thomas Delong witnessed the accident and gave testimony and the case was dismissed. (1)

One Sunday afternoon in January 1862, Fred was out riding when he came to a gully which he thought his mare would jump. However, she propped and refused the leap, thus Fred was flung forward landing on his shoulder. A doctor was sent for, at which time he was bled (bloodletting was a common medical practice and cure). As there was no fracture, just bruising, he was expected to make a good recovery. (2)

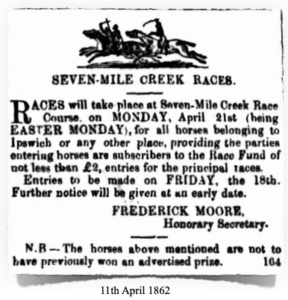

For several years from 1862, Fred held race meetings on his property at the Seven Mile on occassions like Easter Monday, Boxing Day, New Years Day and the Queen’s Birthday.

The Seven Mile Creek Races. St. Patrick’s Day. 17th March 1862 –These races, although hastily got up, were conducted with spirit, and very well attended. At the time for starting the first race there was between two and three hundred people on the ground. For this race prize, £25, three horses started, and after a dashing contest were placed in the following order: Mr. Donaldson’s c.g. Dancer, 1; Mr. Jacob’s Lancer, 2 ; Mr. Watt’s b.f. Black Bess, 3. The second race prize, £15 was won by Mr. Barlow’s black mare, beating Mr. Jacob’s Ladder. After these two, Hurry-Scurrys were run, and for each of which five horses started. The first was won by Mr. Peacock’s chestnut mare, and the second by Mr. D. Downey’s Flying Buck. Great credit is due to the gentlemen who initiated and conducted the sport. Everything passed off creditably, and to the satisfaction of those present. It appears that young Brennan, who met with an accident during the races, was very seriously injured, and remains speechless.

The Seven-Mile Creek Races. 21st April 1862—The only Easter amusements kept up were some races at the Seven-mile Creek, which were well attended and passed off without any accident. There were three races. In the first a mile and a half race, heats, for £10, entrance £1— there were four entries, namely, Mr. Williams’ Baby, Mr. Hanran’s Snob, Mr. Fletcher’s No-name, and Mr. Mehan’s Somebody; won by Mr. Hanran’s Snob, Mr. Mehan’s Somebody coming in second. The second race was a private match for £20 each horse, three miles, one event. The horses entered were Mr. Watts’ Bessy, Mr. Vowles’ Lancer, and Mr. Donaldson’s Dancer, of which Mr. Watts’ Bessy came in winner by several lengths. The third and last race was a Hurry Scurry for £5, in which Mr. Mackay’s Prince came in first, and Mr. M’Grath’s Dandy second. Several others ran, but were not placed.

The White Lion Inn had an array of colourful tenants which resulted in the Moores being embroiled in their troubles;

- In October 1863 the Moores became entangled in a case of sly grog selling due to one of their tenants at the inn. It came about when a man named Charles Brecht was charged with having sold a glass and half (a pint of rum) to Mrs. Jane Walsh when he was not a licensed publican. Sadly Jane was hardly ever sober, and had been living apart from her husband at Moore’s White Lion Inn before the incident occurred. Prior to their parting, the Walshes had lived on the Drayton road about ten miles from Ipswich. Jane’s husband, Kyran Walsh, was also no stranger to the courts. Sly Grog Selling Sly Grog Selling

- Two men, William Barber and James Malcom Munroe, were accused of murdering Mrs Margaret Curtis at Toowoomba on 19th June 1865. Margaret went shopping, and on her return she was murdered in south Ruthven Street, her groceries being scattered about. She had a three week old baby. Barber was arrested in Brisbane Street, Ipswich on 23rd and Munroe was arrested at White Lion Inn at Seven Mile Creek. Munroe had no incriminating evidence on him. He did not say one word, but pretended to be insane. He had allegedly strangled Margaret Curtis for a gold ring which was found in a vest on the road near Seven Mile. The verdict after a trial was that Margaret Curtis “was was wilfully murdered by some person or persons unknown.”

Toowoomba Murder The Late Murder in Ruthven Street

In March 1864, in a major flood, the water was six inches over the handrail of the bridge at the Seven Mile Creek. It was also three feet deep inside the White Lion Inn and the Moores had to climb onto the roof and wait until the water subsided. No doubt the Moores and others in the area had to contend with many inundations of flood waters while living at the Seven Mile.

On the morning of 9th July 1866, the White Lion Inn narrowly escaped destruction by fire. A portion of the premises became ignited by some unknown means, but fortunately the fire was discovered before much damage had been done. Interestingly Fred was not home at the time. In fact he was in police custody. Given the events below, was the fire just a coincidence or an act of revenge?

One week before, on 2nd July, Constable John Elliget, Darby McGrath and Constable Ferry, turned up at the White Lion and searched Moore’s residence. The reason for this search was that Darby McGrath, while looking for his missing bull at the property of James Hallam at Seven Mile Creek, noticed a cow belonging to Mrs Mary Mayne, owner of Rosevale Station, in Fred Moore’s stockyard. (James Hallam worked for Fred Moore.) McGrath checked with John Jones, the station manager at Rosevale, who confirmed that he was missing a cow. Mrs Mayne did not deal in cattle, nor was Jones authorised to sell any beast, so it had to have been stolen.

When the Constable searched Fred Moore’s stockyard he found a red and white cow branded CA near its rump and PM offside and loins, and both ears were slit. There was no doubt about its owner. They could also see that on the same day a beast had been killed in the yard as the remaining offal was still hot. The Constable then went to Moore’s house and demanded that Fred give him the skin of the beast, which he did. The skin was branded with J C the near ribs, and J C with M on another part so he took possession of both the skin and the cow that was branded CA. The cow was identified by McGrath and Isaac Mayne as the property of his wife, Mary Mayne. The skin belonged to John Collins who frequently sold a bullock or cow for meat to Fred Moore. Constable Elliget arrested Frederick Moore that day on a charge of stealing the cow. Fred said, “I did not steal her, I bought her from James Hallam and paid him £7 for her and a bullock”, however, he could not prove this with a receipt.

On 17th July 1866 Fred appeared before the Ipswich Police Court accused of stealing cattle from Mrs Mayne. Mr C. F. Chubb appeared for Fred and maintained there was no case to answer and that the charge had to be strictly proved. Fred was bailed and had to appear when called upon.

Then on 21st November 1866, in the Small Debts Court, the case was heard for Frederick Moore v Mary Mayne. Fred claimed that Mary owed him £32 6s 6d., the amount due for goods supplied to her. The verdict was given for Fred with costs of court. (3)

Consequently, the following February, James Hallam ended up on trial for stealing the cow. Several discrepancies in the evidence were found and the court still didn’t have the testimony of Mary Mayne. Rather than hold Hallam on remand again, they committed him for trial and admitted him to bail of £100, and two sureties of £50 each. On 11th March 1867, James Hallam was brought up before the Court and discharged, no bill (not enough evidence) having been filed against him. (4)

Fred and Sally’s infant son Thomas died of convulsions aged 9 days in April 1870. That year Fred Moore took a two year contract for £28 per annum to deliver the mail twice a week by horseback between Ipswich and the Seven Mile Creek. In May the following was reported in the newspaper.

Mr. F. Moore, who owns the public-house at the Seven-Mile Creek, where the Post Office is situated, has about 8 acres of land under cotton, and 4 of maize. Very little has yet been picked, probably about a bale, the cotton being late, and having been considerably injured by the flood, which covered a portion of it. A fair second crop, however, may be anticipated should the weather continue favourable. The maize is doing very well. (5)

In December 1873, the Inn was yet again involved in another sad incident. Miss Jane Brown, Governess to Mr. John Clarke Foote, was riding from the Seven Mile Creek towards Ipswich accompanied by a Wesleyan minister, William B. Mather, and his brother. The horse she was riding started to canter then gallop. She lost complete control and the horse ran into the bush and crashed against a tree. She hit her forehead, inflicting a large wound and fell from the saddle unconscious. Mr. Mather asked at two houses if she could stay there until a doctor could be called, but he was refused. He was sent on to Mr. Whitney, a farmer at Seven Mile Creek. Mr. Whitney took his dray back to the scene of the accident and carried Miss Brown three miles from the place she fell to Moores’s public-house. Dr. Dorsey and Mr. Foote were sent for. The doctor arrived at 2 o’clock in the morning and did all he could under the circumstances. Jane Brown never rallied. The unfortunate young lady only lingered on until a quarter to 9 o’clock the following morning, at which time she died as a result of a fractured skull. Jane Brown was about twenty years of age and had no relatives in Queensland as far as anyone knew. (6)

Tragedy struck on 8th March 1874. Sally gave birth to a stillborn son and died herself several hours later. Some months before she’d had an accident and it was thought that it may have contributed to her death, but the immediate reason was excessive haemorrhage. The doctor was not summonsed immediately and when Dr. McMullin finally arrived from town, nothing could be done for Sally. She passed away aged 37, leaving her eldest daughters Sarah and Fanny to care for their siblings. Both girls married in 1876. I wonder if one of them took charge of their 5 year old brother Robert?

After 18 years, the license of the White Lion Inn was granted to Joseph Jackson (a carpenter) on 11th June 1878. On 17th September 1879, Joseph was adjudged insolvent, thereby marking the closure of the White Lion Inn.

One last incident was reported before Fred Moore passed from this world. A woman died at Seven Mile Creek on Monday, 20th February 1882. The circumstances prompted the police to hold inquiry into the cause of her death. It was held before Mr. John W. Vance, J.P., in the house of Mr. Fred. Moore, formerly known as the old White Lion Inn. The deceased, Anne Martin, lived in a slab humpy on the opposite side of the road. Her husband, John Martin, a labourer, made his livelihood by working occasionally for the farmers of the neighbourhood.

A reporter wrote : “One would hardly imagine such a lamentable state of affairs could occur in any community, more especially in Rosewood, the well-to-do inhabitants of which had so much consideration shown for their sufferings during the years of drought, when their hardships were so great. The sad tale speaks for itself.”

Here is the report about the inquiry.

From the evidence of Dr. Webb and other witnesses it appeared that the poor woman was near her confinement, and that her life might have been preserved with proper care and attention. The depositions have been forwarded to the Attorney-General. I have never seen a more distressing case of misery and destitution in this happy land, which is said to be literally flowing with milk and honey, and where every man who is willing to work can find employment. The husband of this woman and the father of her children, is a lazy, indolent, almost imbecile creature, who left his wife and children to struggle with poverty, hunger, and dirt, for many years. The house where this family resided is the property of Mr. Donaldson, and consists of two rooms and a shed at the back. There was no furniture of any kind whatever in the house-not even a table, a chair, or a bedstead. The front room was empty. On entering the other room the deceased was found lying on a bundle of rags in one corner of the room. Another bundle of rags in the opposite corner formed the bed of the four unhappy little orphans, who seemed utterly unconscious of the loss they had sustained. They appeared as if the poor mother had taken good care of them, and they should not be left any longer in the hands of a helpless parent like John Martin. I left this sad scene of woe and misery fully impressed with the truth of the saying that one half the world don’t know how the other half lives. I understand that she was interred at the public expense. Allow me, in conclusion, to recommend the intelligent little orphans to the kind consideration of those charitably disposed persons who do good by stealth and blush to find it fame. (7)

Fred Moore died in September 1883. His son, George Henry Moore followed in 1885 aged 17 years.

© Jane Schy, 2024

Sources:

(1) Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser, Friday 8 November 1861, page 3

(2) Courier, Brisbane, Wednesday 29 January 1862, page 3

(3) Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser, Thursday 22 November 1866, page 3

(4) Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser, Tuesday 12 March 1867, page 3

(5) Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser, Tuesday 3 May 1870, page 3

(6) Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser, Tuesday 23 December 1873, page 4

(7) Queenslander, Saturday 25 February 1882, page 231

1851 Census England

England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892

UK Prison Hulk Registers and Letter Books, 1802-1849

New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents, 1788-1842

New South Wales, Australia, Gaol Description and Entrance Books, 1818-1930

New South Wales, Australia, Certificates of Freedom, 1810-1814, 1827-1867