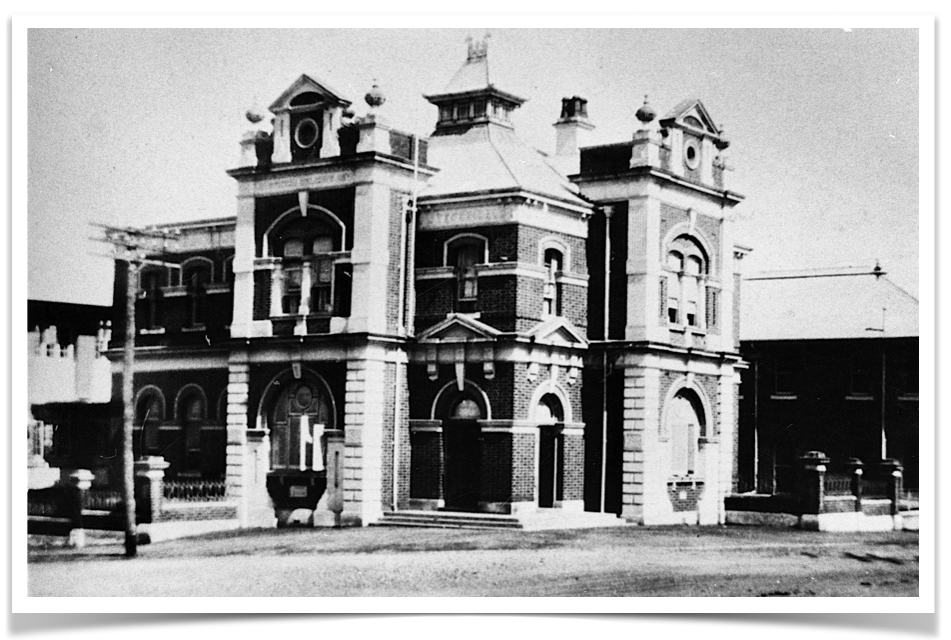

Ipswich Technical College 1927 (Photo: State Library Qld)

Rosewood History

A School Excursion

This account of an excursion to several industrial works by students from the Rosewood State School on 21st August 1925, was written by twelve year old Doris Loveday.

This account of an excursion to several industrial works by students from the Rosewood State School on 21st August 1925, was written by twelve year old Doris Loveday.

It was published in three parts in the Queensland Times. The journalist said, “Her account of the trip, with its varied experiences, is well worth reading.”

We caught the 8.30 a.m. train from Rosewood platform, and enjoyed the train journey to Darra. On either side of the railway line the wild Cunningham wattle was in bloom, and its fragrance filled the air with a sweet, refreshing scent.

Arriving at the Darra Station we walked to the Darra Cement Works, where we were shown over the works by a capable leader, who explained everything as we went along. The limestone is brought by train from Gore to the works, where it is emptied into a trench at the bottom of which are elevators which carry the limestone to a crushing mill. Here it is crushed by large steel balls which rotate and crush the limestone into a powder. These balls wear away gradually, and after six months some are smaller than marbles. Water is added to this powder and it becomes a soft mud.

The clay is found near the premises, and is brought in small trucks to a crushing mill, where it is also crushed into powder. It is then emptied into a pug mill and water is added. A revolving wheel at the bottom stirs the water and clay together till it becomes clay slurry. It is pumped  through a pipe into a large mill where the limestone, in its wet state, lies. These two muds are stirred together, and are finally emptied into silos where the liquid, for now it is such, is agitated by compressed air. After it has been agitated enough it passes into a kiln about 150 feet long. Particles of ground coal are blown into this, and the coal immediately blazes. This mixture passes into a furnace at the other end, where it finally comes out as clinker. As it comes out of the kiln it is red hot so a steam draught is made which cools it off. A man with a shovel stands at the end, and any large pieces of red hot clinker are promptly disposed of.

through a pipe into a large mill where the limestone, in its wet state, lies. These two muds are stirred together, and are finally emptied into silos where the liquid, for now it is such, is agitated by compressed air. After it has been agitated enough it passes into a kiln about 150 feet long. Particles of ground coal are blown into this, and the coal immediately blazes. This mixture passes into a furnace at the other end, where it finally comes out as clinker. As it comes out of the kiln it is red hot so a steam draught is made which cools it off. A man with a shovel stands at the end, and any large pieces of red hot clinker are promptly disposed of.

The clinker is of a grayish black colour. It is taken in these buckets into a mill, where It is crushed and gypsum added. The gypsum prevents the cement setting too quickly. After these have been crushed enough we get the finished article-the cement.

The bags being filled was another interesting process. The bags are sewn up, all but one corner, which is tucked under. The bag is attached to a machine, and the cement runs in. As it fills up the cement pushes up the flap and the man merely loosens it, and it falls on a belt which moves continuously and carries it along to the end.

We visited the chemical room, and we were shown a shaped cement figure. This figure was put between the jaws of a machine and a weight attached to the end was gradually filled with shot until the figure, which was an inch square in the middle, broke. The first figure was three parts sand and one part cement. The weight it was supposed to break at was 200 pounds, but this particular one broke at 340 lb. This shows what fine cement it was made of. Another figure of the same shape, but which had been soaked in water for a day, was tested. This one was to break at 400lb. but it broke at 625lb. (pure cement). This is another example of the fine cement used. A square piece of cement was placed between a compressing machine, and one of our boys turned a handle which gradually made the machine press on the square figure. The weight at which it was supposed to be shattered was two tons, but 17 tons was the weight at which this one broke. It was still moist in the middle, however, so most probably it would have taken much more to break it. had it been quite hard. It was altogether an interesting process.

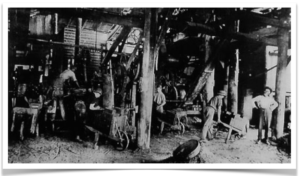

After we had our dinner we walked to Brittain’s Brick, Pipe, and Earthenware Co., where we also spent an enjoyable time. We first visited the quarry from where the clay is taken. It was a huge pit, and the men working below looked rather small. The clay is taken from the pit to a crushing machine, where it is crushed and water added. This mixture forms a clayey mud. A wheel revolves and the mud is placed into a hole the exact size of a brick. Another machine pushes those bricks up and passes them on to a machine which brands them. A man takes the bricks as they come out and places them on a barrow. They are then taken to the stack and are left to harden. When sufficiently hardened they are taken to the kiln where they are roasted. Some of the children went inside this kiln and noticed the arched roof was glazed by the heat of the fire. The bricks, pipes. &c., that were in the kiln were also roasted and glazed. The pipe making machine was not in perfect order, but a few pipes were made so that we could see the method. The mud is placed in the machine and made the required shape. They rare also roasted in the kiln. Another interesting thing was the making out of clay of sewerage necessities. They were made by hand and the work showed great credit to the worker.

After we had our dinner we walked to Brittain’s Brick, Pipe, and Earthenware Co., where we also spent an enjoyable time. We first visited the quarry from where the clay is taken. It was a huge pit, and the men working below looked rather small. The clay is taken from the pit to a crushing machine, where it is crushed and water added. This mixture forms a clayey mud. A wheel revolves and the mud is placed into a hole the exact size of a brick. Another machine pushes those bricks up and passes them on to a machine which brands them. A man takes the bricks as they come out and places them on a barrow. They are then taken to the stack and are left to harden. When sufficiently hardened they are taken to the kiln where they are roasted. Some of the children went inside this kiln and noticed the arched roof was glazed by the heat of the fire. The bricks, pipes. &c., that were in the kiln were also roasted and glazed. The pipe making machine was not in perfect order, but a few pipes were made so that we could see the method. The mud is placed in the machine and made the required shape. They rare also roasted in the kiln. Another interesting thing was the making out of clay of sewerage necessities. They were made by hand and the work showed great credit to the worker.

We left the brick works now to catch the train for Ipswich where we were shown over the “Queensland Times” Office by Mr. Lingard. Several rolls of paper were about the floor and Mr. Lingard said they were brought from England, though he did not see why they should be, considering that we could make them in Australia, and save the expense and trouble of bringing it 13,000 miles across the sea. The paper machine could hold sixteen sheets of paper, four in each place, and the paper was brought over and in between the machine so that it did everything and the human hand had only to set and pick up the paper ready for use. The rolls of paper are placed at one end and the folded paper comes out of the other. About 8,000 papers an hour are produced. The rolls of paper weigh about five hundredweight and five rolls are needed for each edition.

First we were shown a flong made of blotting paper and tissue paper and on this was the news that would eventually be. On the page of the paper. Metal is poured on this is and a stereo sheet is produced semicircular in shape, and the back ribbed and the front printed in outstanding type. This is placed on a roll and printer’s ink is rolled over it. The sheet of paper passes over this and the type is stamped on it.  We walked upstairs and saw the Linotype machines at work. Several linotype operators sat at various machines at work, and worked the keys like a typewriter. The linotype machine is indeed wonderful. A sort o hand comes down when a lever is pressed and picks up the types, carries them along the back of the machine and drops them into their proper compartments for further use. Most of us were given our names in the type. We also saw some of the pictures that would appear in Saturday’s issue and were kindly told how they were produced.

We walked upstairs and saw the Linotype machines at work. Several linotype operators sat at various machines at work, and worked the keys like a typewriter. The linotype machine is indeed wonderful. A sort o hand comes down when a lever is pressed and picks up the types, carries them along the back of the machine and drops them into their proper compartments for further use. Most of us were given our names in the type. We also saw some of the pictures that would appear in Saturday’s issue and were kindly told how they were produced.

We next visited the “Queensland Leader Coy” and saw the making of a modern catalogue. It was all very interesting, especially the three colour process work. Eight sheets at a time were produced, and one side at a time was printed. Thousands of pages lay in stacks on the floor. The three colour work was for the cover, and the man in charge told us how it was done. A stereo is first produced in light blue, then another one in deep yellowish brown. These two are then worked together, forming a picture. Another stereo is made, forming the outline only, in bronze blue. This is worked on also, forming a complete picture. The wrappers for sweets and chocolates were also being made.

Going upstairs we found a room almost like that at the “Queensland Times” Office where several men were working on linotypes. We were given our names here also. We saw the catalogues being folded and sewn, and a line ruling machine. The piece of plain paper is pushed through, and blue paper dipped in ink placed on a roll at the top. Several spikes face downwards and catch this ink and make parallel and horizontal lines on the pages. The guillotine was a paper cutting machine which levels off the pages.

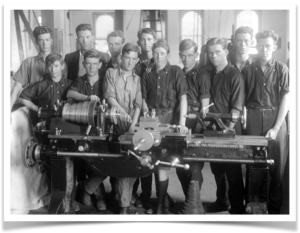

Our last visit was to the Technical College. We went through the various class rooms and saw many things that are not seen in State schools. The laundry is a large room for such a purpose and the girls do all the ironing and folding there. The Kitchen has many gas stoves and every possible equipment to make the work easy. The scullery was kept in good order and the dining room and washing up rooms were scrupulously clean. The drawing room and bedroom were properly and nicely furnished, but the girls are taught to be economical. The High School compartment was an airy compartment and afforded plenty of fresh air. The eurythmic room is a large room fitted with piano, stage, chairs, &c. The machinery room was equipped with everything necessary to teach the boys that trade, while the mining and engineering rooms are fitted with models which show everything about the thing they represent. In the typewriting room numerous typewriters were on the desks, and at first sight we knew this was the room for commercial study. The grounds are large and the girls play play tennis or basketball. Those who do not care for outdoor games may play bobs, quoits or ping pong. Altogether the College is splendidly fitted out and the Ipswich children have a chance of education that is not offered to many others in the State. We caught the 6.15 p.m. train for home, tired, but happy after our splendid day’s trip.

Our last visit was to the Technical College. We went through the various class rooms and saw many things that are not seen in State schools. The laundry is a large room for such a purpose and the girls do all the ironing and folding there. The Kitchen has many gas stoves and every possible equipment to make the work easy. The scullery was kept in good order and the dining room and washing up rooms were scrupulously clean. The drawing room and bedroom were properly and nicely furnished, but the girls are taught to be economical. The High School compartment was an airy compartment and afforded plenty of fresh air. The eurythmic room is a large room fitted with piano, stage, chairs, &c. The machinery room was equipped with everything necessary to teach the boys that trade, while the mining and engineering rooms are fitted with models which show everything about the thing they represent. In the typewriting room numerous typewriters were on the desks, and at first sight we knew this was the room for commercial study. The grounds are large and the girls play play tennis or basketball. Those who do not care for outdoor games may play bobs, quoits or ping pong. Altogether the College is splendidly fitted out and the Ipswich children have a chance of education that is not offered to many others in the State. We caught the 6.15 p.m. train for home, tired, but happy after our splendid day’s trip.

About Doris…

Doris Elizabeth Loveday was born 14th June 1913 in Rosewood and was the daughter of Arthur James Loveday and Ivy Maud Collett, “Ashwell Villa”, John Street, Rosewood. In March 1929, Doris was appointed to the staff of the Gatton High School as a student teacher of commercial subjects. In early September 1932 she left Gatton by the western mail train on transfer to Charleville. She sat for an accountancy examination conducted by the Federal Institute. Doris secured first place in Queensland in the bookkeeping section, second in auditing, and was successful in the mercantile section. Gordon Chalk, also from Rosewood, came first in the auditing section.

On Easter Saturday in 1937, Doris Loveday A.F.I.A. married Norman Archie Charles Goddard at the Rosewood Congregational Church. Norman came from Walhalla, Victoria and was a School Teacher on the Gladstone State School staff. After their honeymoon the couple returned to Gladstone to live.

On Easter Saturday in 1937, Doris Loveday A.F.I.A. married Norman Archie Charles Goddard at the Rosewood Congregational Church. Norman came from Walhalla, Victoria and was a School Teacher on the Gladstone State School staff. After their honeymoon the couple returned to Gladstone to live.

Norman enlisted in the A.I.F. in 1939 and served with the rank of Staff Sergeant (QX16001) in Royal Australian Corps of Signals. Doris came home to stay with her parents in Rosewood about a year later. Norman worked in the cipher section in Papua New Guinea in 1943. This is when the Allies were occupying several islands in the New Guinea chain, but the Japanese still maintained a large base at Rabaul on the island of New Britain. In January 1944, the Australian 9th Infantry Division uncovered the Japanese 20th Division’s entire cryptographic library in Sio, New Guinea. This discovery allowed the signals intelligence section to master the Japanese Army’s codes and ciphers and provide timely intelligence to Allied forces.

Norman was discharged at the end of 1945.

Doris and Norman died in 1992 and 1974 resp. and are interred at the Mount Thompson Memorial Gardens.

© Jane Schy, 2024